My latest 3QD essay is a bit of a wild one. I start by talking about Goodhart’s Law, a quirk of economics that I think has implications elsewhere. I try to link it with neuroscience, but in order to do so I first construct an analogy between the brain and an economy. We might not understand economic networks any better than we do neural networks, but this analogy is a fun way to re-frame matters of neuroscience and society.

Here’s an excerpt:

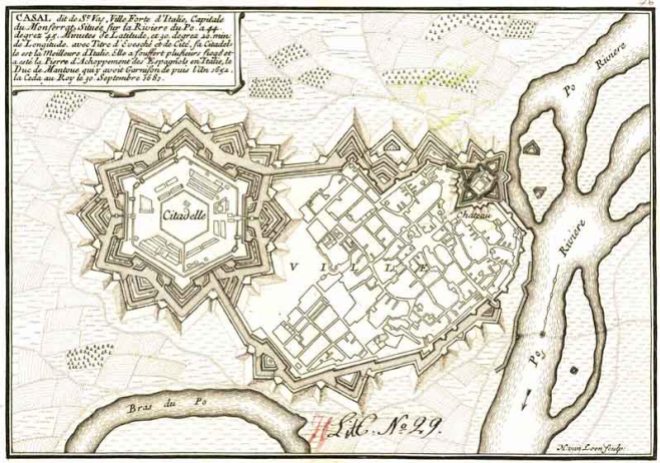

The Neural Citadel

Nowadays we routinely encounter descriptions of the brain as a computer, especially in the pop science world. Just like computers, brains accept inputs (sensations from the world) and produce outputs (speech, action, and influence on internal organs). Within the world of neuroscience there is a widespread belief that the computer metaphor becomes unhelpful very quickly, and that new analogies must be sought. So you can also come across conceptions of the brain as a dynamical system, or as a network. One of the purposes of a metaphor is to link things we understand (like computers) with thing we are still stymied by (like brains). Since the educated public has plenty of experience with computers, but at best nebulous conceptions of dynamical systems and networks, it makes sense that the computer metaphor is the most popular one. In fact, outside of a relatively small group of mathematically-minded thinkers, even scientists often feel most comfortable thinking of the brain as a elaborate biological computer. [3]

However, there is another metaphor for the brain that most human beings will be able to relate to. The brain can be thought of as an economy: as a biological social network, in which the manufacturers, marketers, consumers, government officials and investors are neurons. Before going any further, let me declare up front that this analogy has a fundamental flaw. The purpose of metaphor is to understand the unknown — in this case the brain — in terms of the known. But with all due respect to economists and other social scientists, we still don’t actually understand socio-economic networks all that well. Not nearly as well as computer scientists understand computers. Nevertheless, we are all embedded in economies and social networks, and therefore have intuitions, suspicions, ideologies, and conspiracy theories about how they work.

Because of its fundamental flaw, the brain-as-economy metaphor isn’t really going to make my fellow neuroscientists’ jobs any easier, which is why I am writing about it on 3 Quarks Daily rather than in a peer-reviewed academic journal. What the brain-as-economy metaphor does do is allow us to translate neural or mental phenomena into the language of social cooperation and competition, and vice versa. Even though brains and economies seem equally mysterious and unpredictable, perhaps in attempting to bridge the two domains something can be gained in translation. If nothing else, we can expect some amusing raw material for armchair philosophizing about life, the universe, and everything. [4]

So let’s paint a picture of the neural economy. Imagine that the brain is a city — the capital of the vast country that is the body. The neural citadel is a fortress; the blood-brain barrier serves as its defensive wall, protecting it from the goings-on in the countryside, and only allowing certain raw materials through its heavily guarded gates — oxygen and nutrients, for the most part. Fuel for the crucial work carried out by the city’s residents: the neurons and their helper cells. The citadel needs all this fuel to deal with its main task: the industrial scale transformation of raw data into refined information. The unprocessed data pours into the citadel through the various axonal highways. The trucks carrying the data are dispatched by the nervous system’s network of spies and informants. Their job is to inform the citadel of the goings-on outside its walls. The external sense organs — the eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin — are the body’s border patrols, coast guards, observatories, and foreign intelligence agencies. The muscles and internal organs, meanwhile, are monitored by the home ministry’s police and bureaucrats, always on the look-out for any domestic turbulence. (The stomach, for instance, is known to be a hotbed of labor unrest.)

The neural citadel enables an information economy — a marketplace of ideas, as it were. Most of this information is manufactured within the brain and internally traded, but some of it — perhaps the most important information — is exported from the brain in the form of executive orders, requests and the occasional plaintive plea from the citadel to the sense organs, muscles, glands and viscera. The purpose of the brain is definitely subject to debate — even within the citadel — but one thing most people can agree on is that it must serve as an effective and just ruler of the body: a government that marries a harmonious domestic policy — unstressed stomach cells, unblackened lung cells, radiant skin cells and resilient muscle cells — with a peaceful and profitable foreign policy. (The country is frustratingly dependent on foreign countries, over which it has limited control, for its energy and construction material.)

The citadel is divided into various neighborhoods, according to the types of information being processed. There are neighborhoods subject to strict zoning requirements that process only one sort of information: visions, sounds, smells, tastes, or textures. Then there are mixed use neighborhoods where different kinds of information are assembled into more complex packages, endlessly remixed and recontextualized. These neighborhoods are not arranged in a strict hierarchy. Allegiances can form and dissolve. Each is trying to do something useful with the information that is fed to it: to use older information to predict future trends, or to stay on the look-out for a particular pattern that might arise in the body, the outside world, or some other part of the citadel. Each neighborhood has an assortment of manufacturing strategies, polling systems, research groups, and experimental start-up incubators. Though they are all working for the welfare of the country, they sometimes compete for the privilege of contributing to governmental policies. These policies seem to be formulated at the centers of planning and coordination in the prefrontal cortex — an ivory tower (or a corporate skyscraper, if you prefer merchant princes to philosopher kings) that has a panoramic view of the citadel. The prefrontal tower then dispatches its decisions to the motor control areas of the citadel, which notify the body of governmental marching orders.

~

The essay is not just about the metaphor though. There are bits about dopamine, and addiction, and also some wide-eyed idealism. 🙂 Check the whole thing out at 3 Quarks Daily.

For the record, there is a major problem with personifying neurons. It doesn’t actually explain anything, since we are just as baffled by persons as we are by neurons. Personifying neurons creates billions of microscopic homunculi. The Neural Citadel metaphor was devised in a spirit of play, rather than as serious science or philosophy.

Leave a Reply