In his book The Crest of the Peacock, George Ghevarghese Joseph documents how the popular picture of the mystical, irrational Orient and the logical, rational Occident breaks down when you actually look at the history of the spread of mathematical ideas. He starts with the tired old “Greeks Did Everything First” narrative, and then gradually builds up a more complex — and more accurate — picture of how mathematical ideas spread and evolved.

In his book The Crest of the Peacock, George Ghevarghese Joseph documents how the popular picture of the mystical, irrational Orient and the logical, rational Occident breaks down when you actually look at the history of the spread of mathematical ideas. He starts with the tired old “Greeks Did Everything First” narrative, and then gradually builds up a more complex — and more accurate — picture of how mathematical ideas spread and evolved.

Here I’m going to show you some of the diagrams he used to help illustrate his case:

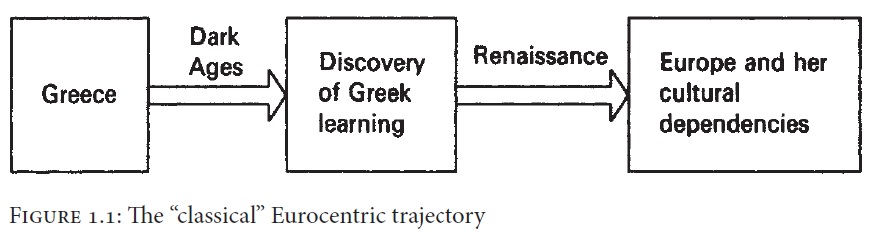

The first figure depicts the standard Eurocentric trajectory that prevailed until very recently, and still dominates the minds of many people both in the West and in other parts of the world. Whenever you read a pop science article in which the only nod to history is a reference to some old Greek thinker, you should wonder whether the writer was just too lazy to check if the same sort of knowledge existed —often earlier — in other parts of the world.

The second trajectory is a major improvement on the first. It acknowledges that Egypt and Mesopotamia were major sources of Greek knowledge. If fact the ancient Greeks themselves admit this, so the persistent partial blindness of the first trajectory must have had something to do with colonial-era notions of racial and cultural superiority. But the second diagram still makes it seem like the Greeks were the main players in the pre-modern history of mathematics, and that the Arabs served merely as an external hard drive for Greek knowledge, keeping it warm for the Europeans during their “Dark” Ages.

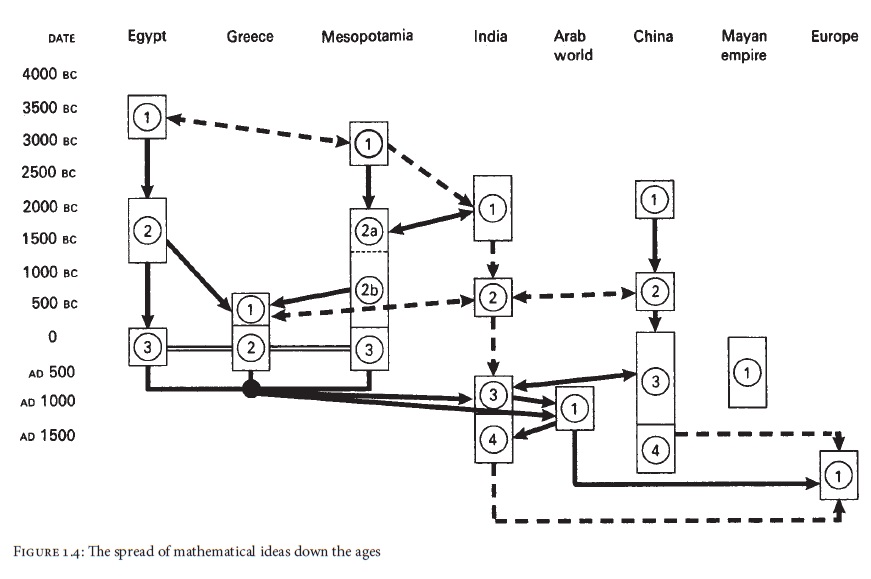

If we look more closely at the so-called Dark Ages, we see that there was actually a lot going on — just not in Christian Europe. Major advances in mathematics, including the origins of algebra and trigonometry, were occurring in India, China and the Muslim world. And of course, the pivotal discovery of zero and the related development of the decimal place system, happened outside of Europe.

So if we combine our insights about the ancient world with our new understanding of the “Dark” Ages, we come up with a new diagram in which Europe is no longer the center of the mathematical universe.

This diagram is complex enough to require an elaborate key:

All this is not just a matter of dead history. The way cultures see themselves and others in the present is strongly wrapped up in history. When Europeans and their descendants claim all of science and rationality for themselves, they implicitly claim that other cultures are inferior. This attitude, when combined with colonialism and its many legacies, has a profound impact on postcolonial cultures. The responses of the formerly colonized are pulled between two extremes: a repudiation of “Western” rationality and an embrace of the worst forms of conservative obscurantism, or an attempt to “modernize” and dispense will all ancient customs in an attempt to “catch up” with the West. If we realize that the story of human knowledge has always been a collaborative effort, we can dispense with the absurd idea that some particular culture or race has a monopoly on fundamental truths.

I haven’t finished reading The Crest of the Peacock, but I highly recommend it. It’s a very important corrective and can have a powerful inspirational impact on young people in the postcolonial world. It can also help fight the rising tide of cultural chauvinism and outright racism in Europe and America, as well as the various fundamentalist reactions in the rest of the world.

_____

For math geeks: The book also raises the intriguing possibility that a key step in the discovery of calculus was made in India in the late middle ages. Between the 14th and the 16 centuries, the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics made major advances, including the earliest discovery of infinite series techniques. There is no solid proof, but circumstantial evidence supports the idea that Catholic missionaries — who were explicitly on a mission to gather native knowledge wherever they went — found out about these advances and took them to Europe, where they percolated and perhaps contributed to Newton and Leibniz’s later discoveries. We may never know the truth of the matter.

Leave a Reply