I wanted to write a post on a new fMRI paper that looks really interesting. But in attempting to do so I felt the need to condense some of my own cloudy thoughts on fMRI. Think of this as one part explanation, one part rant, and one part thinking aloud.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become a popular tool for human neuroscience and experimental psychology. But its popularity masks several major issues of interpretation that call into question many of the generalizations fMRI researchers would like to make. These generalizations often lead to overzealous and premature brain-centric redefinitions of high-level concepts such as thinking, emotion, love, and pleasure.

Sensationalist elements in the media run with these redefinitions, taking advantage of secular society’s respect for science in order to promote an unfounded reductionist attitude towards psychological and cultural phenomena. A reductionist attitude feeds off two often contradictory human desires: one for simple, intuitive explanations, and the other for controversial, novel solutions. This biased transfer of ideas from the laboratory to the newspaper, the blog and the self-help book is responsible for a rash of fallacious oversimplifications, such as the use of dopamine as a synonym for “pleasure”. (It correlates with non-so-pleasurable events too.)

Neuroscientific redefinitions of high-level phenomena, even when inspired by an accurate scientific picture, often fall prey to the “mereological fallacy“, i.e., the conflating of parts of a phenomenon for the whole. Bits of muscle don’t dance, people do. And a free-floating brain doesn’t think or feel, a whole organism does.

But before dealing with the complex philosophical, sociological and semantic issues posed by neuroscience, we must be sure that we understand what the experimental techniques are actually telling us. fMRI experiments are usually interpreted as indicating which parts of the brain “light up” during a particular, task, event, or subjective experience. For instance, a recent news headline informs us that “Speed-Dating Lights Up Key Brain Areas“. The intuitive simplicity of such statements masks a hornets’ nest of interpretation problems.

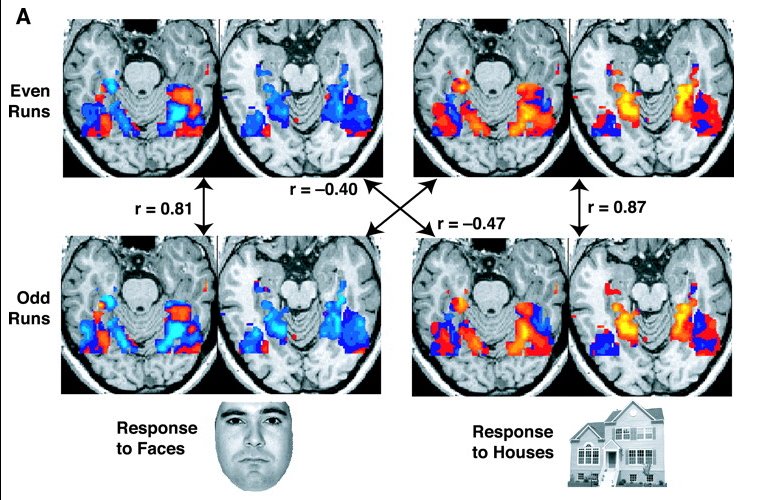

What does an fMRI picture represent? fMRI results only reach statistical significance if the studies are carried out in a group of at least 5-10 people, so the “lighting up” is reliable only after pooling data [But see the edit below]. And in addition to averaging the data from multiple subjects, usually the experimenter must also average multiple trials for each subject. So the fMRI heat-map is an average of averages. Far from being a snapshot of the brain activity as it evolves through time, an fMRI heat-map is like a blurry composite photograph produced by superimposing several long-exposures of similar, non-identical things.

As if this were not problematic enough, the results of an fMRI scan of a single person must be subtracted from a baseline before further analysis. The brain is never quiescent, so to find out about activity in a particular region during a particular event or task, the experimenter must design a control that is identical to the task except with respect to the phenomenon of interest. Imagine a boat with three people on it, sailing on choppy seas. If an observer watching calmly from the shore wants to understand how each person is moving on the boat, she must first factor out the overall motion of the boat caused by the waves. Only then can the observer determine, say, that one person on the boat is jumping up and down, the other is swaying from side to side, and the third is trying to be as still as possible. The subtractions used in fMRI studies are like the factoring out of the motion of the boat — they allow the experimenter to zoom in on the activities of interest and ignore the choppy sea that is the brain’s baseline activity.

Here’s another analogy that might help (me) understand what’s happening with fMRI averaging and subtracting. Let’s say you want to understand the technique of baseball batters that allows them to successfully hit a particular kind of pitch. You take videos of 20 batters hitting, say, a fastball. The fastball is the “task”, and each attempt to hit the ball is a “trial”. Suppose each batter makes 100 swings, and around 50 connect with the ball. The rest are strikes. So there are 50 hits and 50 misses. You take the videos for the 50 hits and average them, so you get a composite or superimposed video for each batter. Then you take the videos of the 50 strikes, and average those. This is the control. Now you “subtract” these two averaged videos, for each batter, getting a video that would presumably show a series of ghostly images of floating, morphing body parts — highlighting only what was different about the batter’s technique when he made contact with the ball versus when he didn’t. In other words, if the batter’s torso moves in exactly the same way whether he hits or misses, then in the video the torso will be subtracted out, and only the head, arms and legs will be visible. Finally, you pool together the subtracted videos for all 20 batters and average them. Now you have a single video that shows the average difference in batting technique between successful hits and misses. If you’ve done everything right, you have some idea of which batting techniques tend on average to work against fastballs.

But consider what may be misleading about this video. Perhaps there are two different techniques or strategies for hitting a fastball. The averaged video will only show a kind of midway point between them. Basically, individual differences can get blurred out by averaging. So sometimes the batting technique that seems to be suggested by the average doesn’t really exist — it can be an artifact of averaging, rather than a picture of an actual trend. Good statistical practices help experimenters avoid artifacts, but as the task and the stats become more complicated, the scope for misunderstanding and misuse expand. In other words, every mathematical angel is shadowed by its very own demon.

Another interpretation issue has to do with what the subtraction means. In the case of the missing torso, you can assert that the difference between success and failure at hitting a fastball does not depend on the torso’s movement, since it’s the same regardless of what the batter does. But this does not mean, however, that the torso has nothing to do with batting. After all, we know the torso is what links up everything else and provides the crucial central services to the arms and legs. So if a brain region doesn’t light up in an fMRI study, this doesn’t mean that it has no role to play in the task being studied. It may in fact be as central to the task as the torso is!

But the problems associated with averaging and subtraction crop up in all forms of data analysis, so they’re among the inevitable hazards that go with experimental science. The central question that plagues fMRI interpretation is not mathematical or philosophical, it’s physiological. What neural phenomenon does fMRI measure, exactly? It seems a partial answer may have been found, which I’ll touch on, hopefully, in the next post.

____________________

Notes:

- William Uttal’s book The New Phrenology (which I have only read a chapter or so of) describes how the “localization of function” thread that runs through fMRI and other neuroscientific approaches may be a misguided return to that notorious Victorian pseudoscience. Here is a precis of the book.

- This New Yorker piece deals with many of the issues with fMRI, and also links to related resources including a New York Times article.

- Neuroscience may not be as misleading to the public as was originally thought. Adding fMRI pictures or neurobabble was thought to make people surrender their logical faculties, but a recent study suggests that the earlier one may have been flawed.

- For a vivid illustration of the potential effects of averaging, check out this art project. The artist averaged every Playboy centerfold, grouping them by decade, producing one blurry image each for the 60, 70s, 80s, and 90s. Don’t worry, it’s very SFW.

- You can also play around with averaging faces here.

____________________

EDIT: In the comment section Kayle made some very important corrections and clarifications:

“You say that fMRI results only reach statistical significance if the studies are carried out in groups. This is not quite right. Almost all fMRI studies begin with a “first-level analysis,” which are single-subject statistics. This way you can contrast different conditions for a single subject. With large differences, small variablity, and enough trials, robust maps can be created. This is done for surgical planning when doctors are considering how much brain they can resect surrounding a tumor without endangering someone’s ability to move or talk. When examining mean differnces between groups, however, you need to examine results from multiple people (“second-level analysis”). Again, this is not specific to fMRI. The rule of thumb goes something like this: Most people are interested in being able to detect differences with effect sizes of about 1 SD or above. To do this with some confidence (Type II p < 0.20) you need about 10 to 30 observations per group.”

also

” Every fMRI result you’ve seen includes single-person single-session results that generally are not reported because most people aren’t interested.”